Spotify’s Profit Problem: The Truth Behind Its €3B in Losses

Inside the licensing trap, podcast pivot, and endless losses of a streaming giant.

Let’s talk about the company that saved the music industry (and is still somehow broke):

Spotify.

The app we all use. The brand that turned music into a monthly subscription. The platform that made it feel normal to stream Taylor Swift at 7AM in the shower and Bad Bunny at 2AM in the club.

It’s one of the most culturally powerful tech companies of our time. And until 2024, it had never turned an annual profit.

Let that sink in.

Despite over 220 million paying users. Despite over €11.5 billion in annual revenue. Despite basically rebuilding the entire music economy from scratch...

Spotify had lost nearly €3 billion since it was founded.

How is that even possible?

Let’s dig into the numbers, the structure, the industry, and the power plays behind the Spotify paradox.

Because what looks like a slick subscription business is actually a giant economic tug-of-war — and Spotify had been losing for almost 20 years.

Back to 2006

Back in 2006, the music industry was flatlining. CD sales were crashing. Piracy was everywhere. People weren’t just stealing music — they were normalizing it.

Then a 23-year-old Swede named Daniel Ek shows up with a wild pitch: access every song ever made, anytime, for just ten euros a month. No downloads. Just streaming.

It worked. Like, really worked.

By 2014, Spotify had 40 million users. Today, it's over 550 million. Of those, 220 million pay. And the product isn't just popular, but culture. Playlists dominate listening habits. Albums barely matter. Release cycles bend around Spotify’s algorithm. Even the songs themselves are shorter. More hooks, less intros. Everything is built for skips and streams.

But the better Spotify gets at what it does, the more money it loses.

Spotify doesn’t own the music it streams. It rents it. From the three mega-labels that run the industry: Universal, Sony, and Warner.

Together, they control around 70% of all global music rights. If Spotify wants to offer Taylor Swift, Drake, or The Weeknd, it needs to pay up. No label deal, no music.

In 2022, Spotify paid nearly €8 billion in licensing fees. That’s 70% of its entire revenue.

To put it differently: if you pay 10 euros for your subscription, 7 of those go straight to the music industry. Before Spotify even gets to cover marketing, R&D, servers, or paying people.

Burning cash per user

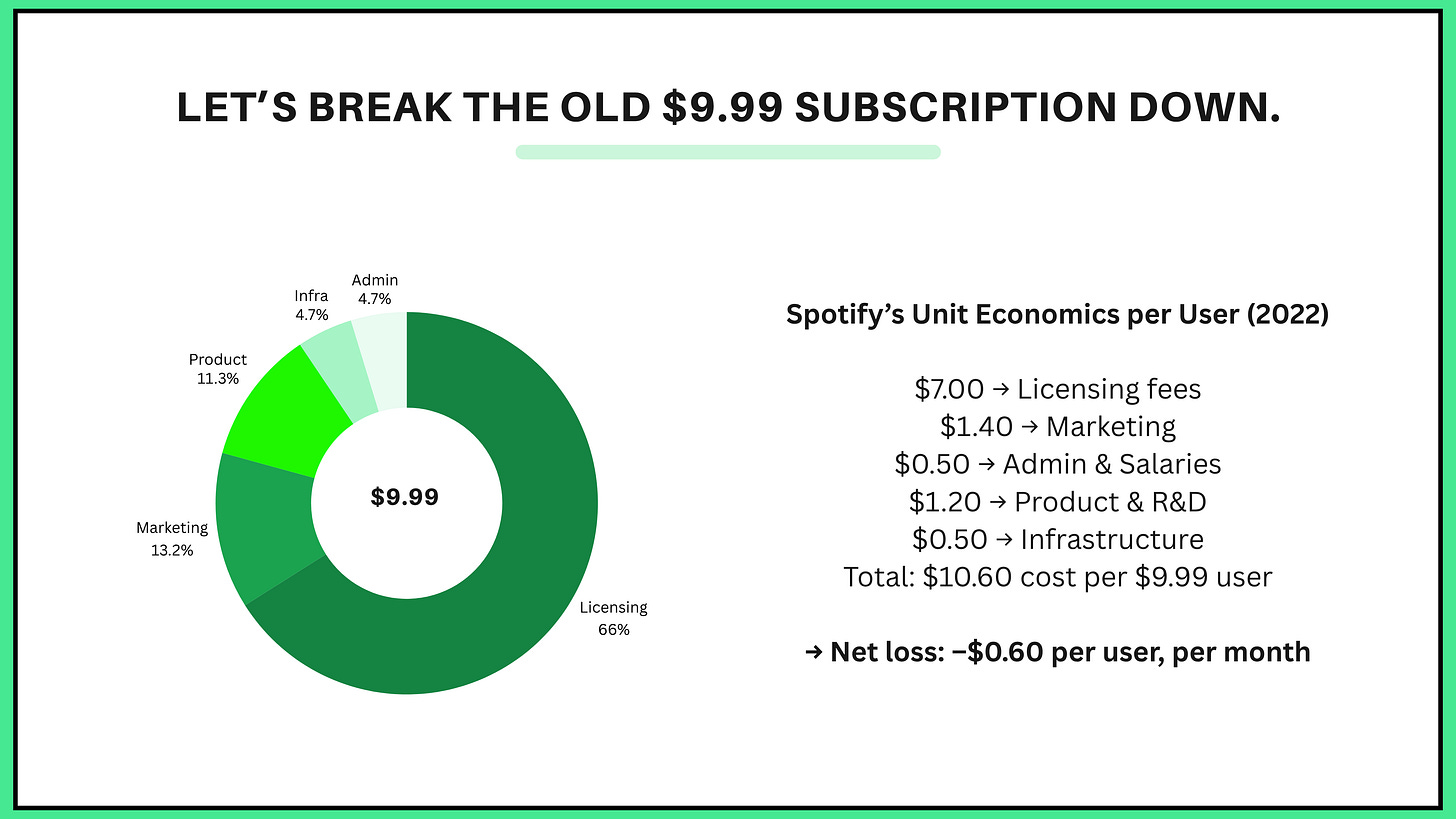

Let’s break it down. That old 9.99 subscription?

About 7 euros go to licensing. 1.40 to marketing. 1.20 to product development. 0.50 to infrastructure. Another 0.50 to admin and salaries.

That leaves Spotify with a loss of about 60 cents per user. Every single month.

In theory, adding more users should help. But here’s the problem: those licensing fees are proportional. As revenue grows, costs grow. There’s no margin of safety. No economies of scale. No leverage.

And that’s where the Netflix comparison breaks.

Why Netflix can, and Spotify can’t

Netflix used to pay studios just like Spotify pays labels. But then it pivoted. It started making its own content. House of Cards was first. Then Stranger Things. Now, over 50% of Netflix’s US library is in-house.

As a result, licensing costs dropped to 24%. Margins widened. The business scaled.

Spotify can’t do that. The labels saw it coming. Their contracts block Spotify from signing or developing its own music talent.

No originals. No IP. No Taylor Swift of their own.

Spotify is stuck as a middleman. And middlemen don’t win in the long run.

No moat, no mercy

Making matters worse: Spotify has no moat. No unique advantage. Apple Music offers the same catalog. So does YouTube Music. So does Amazon.

Unlike streaming video, music isn’t driven by exclusives. You don’t need five services. You need one. And they all offer the same songs.

If Spotify loses a label or artist? Users just switch apps. Loyalty is thin. Differentiation is nearly impossible.

And here’s the kicker: Spotify’s competitors don’t even care about profitability.

Apple Music is a feature inside Apple’s services bundle. Amazon Music is a bonus inside Prime. YouTube Music exists because Google likes to sprinkle products into its ad machine.

Spotify doesn’t have that luxury. It has no ecosystem. No hardware. No cloud business. No e-commerce operation. Streaming is the business.

The podcast pivot

That’s why Daniel Ek made a pivot. He called it Audio First. And it meant: less music, more podcasts.

Over a billion euros went into this shift. They bought studios. Signed big exclusives. Joe Rogan. Kim Kardashian. Prince Harry and Meghan. German shows like Fest & Flauschig and Gemischtes Hack.

Podcasts were supposed to be the answer. Spotify could own the rights. Avoid paying the labels. Sell ads. Boost margins.

In theory: a great move.

In practice? Messy.

Some shows were expensive duds. Others became toxic or controversial. In 2021 alone, Spotify lost 100 million euros on podcasts.

By 2024, the exclusivity model was already being watered down. Many shows were released across platforms again, just to recoup ad spend.

Even Ek admitted they overpaid.

But here’s the thing: Spotify doesn’t really have a choice. Podcasts may be the only chance they have to build a business with real margins.

They also finally raised prices. In 2024, the individual plan went from 9.99 to 10.99.

But it might be too little, too late. Most users are on family plans anyway. Spotify earns just €4.52 per user on average.

That doesn’t give you much to work with when your licensing costs alone eat up 70%.

Spotify changed everything. Except its margins.

Spotify built a revolutionary product. No question. They changed how we consume music. Maybe even saved the entire industry. They redefined what an album is. Made it possible for an artist to blow up without a label. They launched careers, shaped genres, and rewired how we listen.

They turned data into fandom. Turned habits into rituals. Turned Wrapped into a cultural moment.

But the business underneath? Still fragile.

After nearly two decades of losses, Spotify finally posted its first annual profit in 2024 — over a billion euros in the black.

It’s a milestone. But not a finish line.

Because the core problem remains:

No control over content. No structural moat. No diversified revenue. And competitors who don’t even need to win in streaming to win overall.

Can podcasts or audiobooks create a lasting margin?

Can Spotify build something defensible — or just survive in the gaps Big Tech leaves behind?

One good year doesn’t fix a broken model.

But it does buy time.

Let’s see what they do with it.

Cheers 🥂

~Jannis

Read now:

Beyond Meat’s Billion-Dollar Miscalculation

Entertaining and educational

I have no business sharing my ideas about Spotify specifically. I do have an interest in ethics, psychology, community design, and character development, though. I’ll take a stab.

I think another version should arise, to decentralize this tech and make it a multi-tool in the harsh environment it lives in. You are right in identifying this “empire”, low receptivity and capability for success.

If this was member owned with tier and PWYW models available, there’s flexibility, accessibility and support

Value-scaling, participatory. So like, listeners/artists/curators/developers should get tokens to “vote” on things like playlist curation albums, revenue split models, featured initiatives for the community, ethical content policies. Each role gets a say in the tools they’re using and how to improve it. It improves over time ethically

It should be transparent and real time. Artists receive payout from their labors and listeners honor what they’re receiving.

Actual usage and impact considered by everyone from different angles

Spotify struggles with competing because these other huge companies can absorb loss, like you say. They simply have one thing going for them, and it’s what they’re providing the community.

We should lean into models that help us support each other and drain the wealth distribution problem. Built more like trees and less like towers

My question is, even if this were laid out in perfect form as a system to create, would anyone participate